They are like little, armored tanks strategically moving up an Army battle map. They are boney, nearly blind, but also strangely beautiful. And, now, they are now in Indiana.

Armadillos have made their return to Indiana after a long-awaited 40,000 years! Surprised, Mr. Eric Jantzen, an EHS Environmental Science teacher, admits he’s learned something new: “I didn’t know they’d been here that long ago!” Delighted that they are here now, Jantzen adds, “Anything that wears its own armor is great in my book!”

But, why Indiana? And, why now? It appears the answer is simply: migration.

Armadillos trace their existence back to South America, living in isolation before the formation of the Isthmus of Panama–now known as the Isthmus of Darien–bridging them with a host of new mammal friends. Some members of the species continued to migrate northward into the southern region of North America during the Great American Interchange, sparking their abundant population and continued migration further into North America. Now, the United States is home to the 9-banded armadillo species.

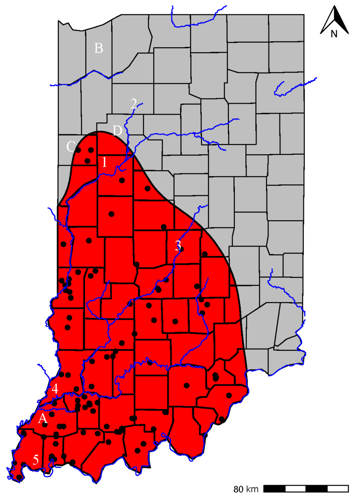

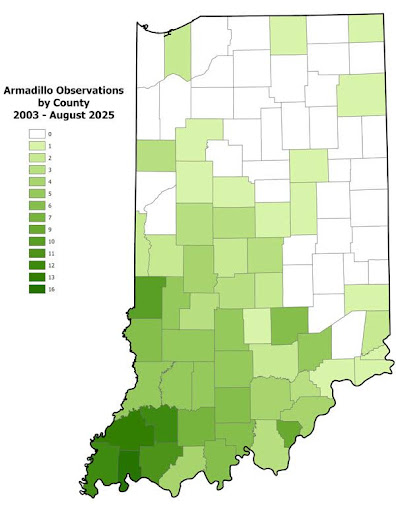

The first sightings of the 9-banded armadillo in this country date back to the mid-1850’s in Texas. Their rapid migration was fostered by their amazing adaptability to foreign terrain. The hot, dry climate, in addition to the habitable soil, made the Southwest prime real estate for these creatures. Over time, however, the armadillos sought greener pastures: better soil and more food supply. It took them about 150 years to get here, but the armadillos found their way into southwestern Indiana by 2003.

With reports of both live and roadkill sightings, armadillos were quickly establishing year-round sightings in the southern half of the state. By 2018, there were reports of their growing population and migration in the northern counties: Allen, Porter, Steuben, and even Elkhart. Mrs. Cara Storer, an EHS Biology teacher, has questions about what their introduction will mean for Indiana. “It will be interesting on how they’ll affect the current wildlife.”

Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources is not overly concerned. Armadillos at heart, the DNR site says, are natural scavengers, finding food nocturnally. Living in forested environments with loose sand and or dirt, they look for smaller creatures, such as ants, termites, grasshoppers, snails, spiders, millipedes, and invertebrates. Armadillos also enjoy the soft, loose soil or sand in order to build their impressive burrow systems for shelter–creating competition primarily with only the mole. Moles are relatively blind creatures that forage for food in a similar way as the 9-banded armadillo. However, armadillos hold the advantage with slightly better sight and a keen sense of smell that enables them to discover insects and rodents significantly quicker than their competition can.

Those who should be more alarmed by the armadillos are the Hoosier farmers and private landowners. Armadillos can damage agricultural crops and landscaped lawns by digging for insects and grubs in fields and yards. However, there is little landowners can do to rid their property of these little invaders. Under Indiana Administrative Code (312 IAC 9-3-18.5), the 9-banded armadillos may not be trapped, or killed, unless they have destroyed or caused “substantial damage” to property. If damage has been caused, property owners can remove the armadillo without permit, or they can request a trained handler to do it.

Those who should be more alarmed by the armadillos are the Hoosier farmers and private landowners. Armadillos can damage agricultural crops and landscaped lawns by digging for insects and grubs in fields and yards. However, there is little landowners can do to rid their property of these little invaders. Under Indiana Administrative Code (312 IAC 9-3-18.5), the 9-banded armadillos may not be trapped, or killed, unless they have destroyed or caused “substantial damage” to property. If damage has been caused, property owners can remove the armadillo without permit, or they can request a trained handler to do it.

Mrs. Heather Kidder, an EHS Agricultural Science teacher, warns average citizens to never attempt removing or handling an armadillo on their own. “It’s a dangerous thing. People around here aren’t quite familiar with them.” Until hearing this, Sophomore Allison Kissel would have been tempted to pick up one. “They’re just cute pill bugs with big ole ears!” she expresses. Even though these little armadillos can look charming, they are one of few species of animals that can spread the disease of leprosy to humans. Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae. The disease affects the skin and peripheral nerves and, if left untreated, can cause “progressive and permanent” disability.

Mr. Josh Bamber, an EHS Agricultural teacher, shares Kidder’s concern: “I certainly wouldn’t touch one in the wild if I saw one!” In addition to the fear of disease, the claws of an armadillo are sharp. Fortunately, in the case of leprosy, the disease is curable nowadays. The best advice is to leave them to the professionals: Complete a Report A Mammal form on the Indiana DNR website when an armadillo is spotted.

Despite armadillos being spotted locally, the likelihood is that their longevity will die out eventually–just as they did 40,000 years ago. The winter climates common to this area will likely prove to be too harsh for their survival, so they will move on. Until then, however, the harshest adversary that an armadillo will likely encounter in the Hoosier State is the bumper of a car.

Fun fact: being hit by cars is the leading cause of death for armadillos.

Other Fun Facts:

- Armadillos have the capability to jump over 3 feet in height when startled.

- The 9-banded armadillos have litters of four identical quadruplets.

- These little guys were once called “Poor Man’s Pork” or “Hoover Hog” during the Great Depression, as the meat is similar in taste to pork, and people were blaming President Hoover for the Great Depression.

- The Pink Fairy armadillo is the smallest, measuring as tiny as 4 inches and weighing as few as 3.5 ounces.

- The Giant armadillo is the largest, measuring as much as 5.9 feet and weighing as much as 176 pounds.

- The 10- stringed South American instrument called a charango is made by using an armadillo shell.

- Armadillos can reach speeds up to 30 miles an hour.

- Armadillos are not afraid of water; in fact, they can also hold their breath for up to six minutes and can walk underwater to cross streams.