BHM: Robert Smalls Made Gigantic Strides

February 25, 2022

Before dawn on May 13, 1862, a black slave named Robert Smalls would make history in less than four hours. In the midst of the Civil War, this black male slave would commandeer an armed Confederate ship and then deliver its 17 black passengers (nine men, five women and three children) from slavery to freedom. As said by Aderrion Mills, a sophomore, “He did an amazing job; he freed 17 slaves in a time where freeing even one was nearly impossible. He’s a real hero!” Who was this brave man?

Robert Smalls was born in 1839 to a woman named Lydia Polite, a black slave owned by Henry McKee. She gave birth to him in a cabin behind McKee’s house, at 511 Prince St. in Beaufort, South Carolina. His mother lived as a servant in the house but grew up under the harsh South Carolina sun in the fields. It is still not clear who Smalls’ father was. It is theorized to be one of the McKee family or one of the individuals who ran the plantation. What is clear is that the McKee family immediately favored Robert Smalls over the other slave children, so much so that his mother worried he would reach maturity without grasping the horrors of the institution into which he was born. To educate him, from a young age, she arranged for him to be sent into the fields to work and watch slaves at “the whipping post.”

At the age of 12, however, things would change for Robert Smalls, as he would be sent to Charleston as a laborer for one dollar a week, with the rest of the wage being paid to his master. Smalls first would work in a hotel, then go on to become a lamplighter on Charleston’s streets. As he matured, his love of the sea led him to find work on Charleston’s docks and wharves. Smalls eventually worked his way up to become a wheelman. As a result, he was very knowledgeable about Charleston harbor.

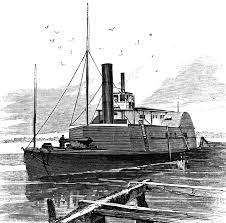

In April 1861, the American Civil War began with the Battle of Fort Sumter in the nearby Charleston Harbor, and Smalls began to have seeds of escape planted in his mind upon first seeing the Union naval blockade, only seven miles northward. A little over one year later, after two weeks of supplying various island points, the C.S.S Planter, the ship Smalls was stationed upon, would come to rest on the Charleston docks for one night. Smalls and a crew composed of fellow slaves, in the absence of the white captain and his two mates, slipped the cotton steamer off the dock, picked up family members nearby, and sailed out into the open sea past multiple Confederate checkpoints–including Fort Sumter–and surrendered their ship to the Union checkpoint. The only way to describe these actions would be heroic, put best by Thomas Davis, a security guard here as Elkhart High School, “In a time where, as a slave, you could be killed for doing anything like this, for him to do what he did was very brave, very heroic, and there’s a large amount of grit there that needs to be recognized.” This is the most talked about portion of Smalls’ life–these four, small hours–but he would go on to do many more things of note in his lifetime.

In April 1861, the American Civil War began with the Battle of Fort Sumter in the nearby Charleston Harbor, and Smalls began to have seeds of escape planted in his mind upon first seeing the Union naval blockade, only seven miles northward. A little over one year later, after two weeks of supplying various island points, the C.S.S Planter, the ship Smalls was stationed upon, would come to rest on the Charleston docks for one night. Smalls and a crew composed of fellow slaves, in the absence of the white captain and his two mates, slipped the cotton steamer off the dock, picked up family members nearby, and sailed out into the open sea past multiple Confederate checkpoints–including Fort Sumter–and surrendered their ship to the Union checkpoint. The only way to describe these actions would be heroic, put best by Thomas Davis, a security guard here as Elkhart High School, “In a time where, as a slave, you could be killed for doing anything like this, for him to do what he did was very brave, very heroic, and there’s a large amount of grit there that needs to be recognized.” This is the most talked about portion of Smalls’ life–these four, small hours–but he would go on to do many more things of note in his lifetime.

Smalls may not have had the funds to purchase his family’s freedom, but upon being taken in by the Union, Congress passed a private bill authorizing the Navy to appraise the Planter and award Smalls and his crew half the proceeds for “rescuing her from the enemies of the Government.” Smalls would receive $1,500, the modern-day equivalent of just over $34,000, though his pay should have been substantially higher. Smalls would go on to pilot as part of Admiral Du Pont’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, engaging in approximately 17 military actions until the war’s end in 1865.

After the war, Smalls would become a first-generation Black politician, serving in the South Carolina state assembly and then senate, and for five nonconsecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1874-1886) as a Republican, before watching his state roll back Reconstruction. He was a large advocate for African-Americans’ political rights and ability to enlist and recruit black soldiers, having famously said, “My race needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country. It proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.” He passed on Feb. 22, 1915, in Beaufort, in the same house he was born behind as a slave.