BHM: Meet The Harlem Hellfighters!

February 4, 2022

May 14, 1918, in the Argonne Forest, France, two soldiers–Private Henry Johnson and Private Needham Roberts–stand alert at Outpost 20, though it is nearly 2 in the morning. Though both are African-American; they wear French helmets and belts over their U.S Army uniforms and carry French rifles. A bullet whizzes by from a nearby hidden German sniper, the first shot fired in a small German attack upon the French outpost. They both hunker down in a dugout and begin to line up grenades to throw, when over the din of gunshots they hear someone cutting through the Outpost’s gate. Private Roberts runs for help, but falls wounded, making his way back to Johnson to begin lobbing grenades. After their supply of grenades runs dry, Johnson switches to his rifle, holding steadfastly against the incoming German assault, even as his rifle jams in his hands. As German soldiers storm into their position, Johnson, refusing to stand down, begins swinging his rifle like a club, until he takes a blow to the head, as well. Fighting to stay conscious, he sees three enemies grabbing Roberts, so he draws his knife and charges, entering into what later would be described as a “berserker rage.” Ignoring gunshots to his face and hands, he fatally wounds the three assaulting his fellow soldier before attacking the remaining German squad with such a fury that they flee in terror. When reinforcements arrive, they find four dead enemies and evidence that he had wounded 10 more. He would be promoted to Sergeant, receive an award from the French, earn the nickname “Black Death,” and become the most legendary member of the Harlem Hellfighters as a result.

The following is an excerpt from the beginning of the three-page paper the New York Tribune ran Feb. 18, 1919, after nearly 3,000 veterans of the 369th Infantry (formerly the 15th New York (Colored) Regiment) marched from Fifth Avenue at 23rd Street to 145th and Lenox. “Up the wide avenue they swung. Their smiles outshone the golden sunlight. In every line proud chests expanded beneath the medals valor had won. The impassioned cheering of the crowds massed along the way drowned the blaring cadence of their former jazz band. The old 15th was on parade and New York turned out to tender its dark-skinned heroes a New York welcome.” One of the few black combat regiments in World War I, they’d earned the prestigious Croix de Guerre from the French army under which they’d served for six months of “brave and bitter fighting.” Their nickname they’d received from their German foes: “Höllenkämpfer,” or the Harlem Hellfighters.

After a draft initiated by the Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, which included all able-bodied men between the ages of 21 and 30, the Governor of New York, Charles Whitman, was the first to implement it fully, appointing veteran Colonel William Hayward to organize the recruitment of an African-American regiment. The men assigned to this new regiment, the 15th Infantry, many of them from Harlem, reported for duty on July 25, 1917, at New York’s Camp Whitman. Initially standing at over 2,000 mostly African-American and Puerto Rican recruits, with nearly another 2,000 on their way thanks to the draft. Training proved difficult for such a large number of individuals due to lack of space, but then they received both good and bad news. The good news? They would be relocated to a suitable training camp. The bad news? It was Camp Wodsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The local reception was expectedly racist.

Meanwhile, in the heart of the war, the French were under pressure and low of men. Calling on the United States for assistance for reinforcements, an entire U.S Brigade under the command of John J Pershing, including the New York 15th Infantry, was shipped to France as an autonomous unit. On Dec. 27, finally the men arrived on French soil. After a few months, to prevent infighting among the brigade between the white and black soldiers, Pershing loaned the 15th Infantry to the 16th division of the French army. Redesignated the 369th Infantry, the French welcomed their help.

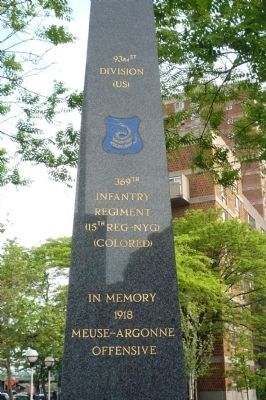

In September, the 369th Infantry forged their legacy. In a fierce battle, they captured the town of Sechault. Holding Sechault gave the Allies a strategic advantage, but the 369th had done almost too good of a job, having outpaced the French troops that were supposed to flank them. But, by the time they were ordered to fall back, they had already stormed 14 kilometers through the German opposition, leaving 851 of their own soldiers dead. It was this event which would finally earn them their moniker, “The Harlem Hellfighters.” The Hellfighters would spend 191 days in combat, more than any other U.S regiment, and though they suffered many casualties, they never once ceded a foot of ground to the enemy, nor were any ever captured alive. After Sechault, the French military awarded 171 Hellfighters the Croix de Guerre for their actions, and a monument to them still stands today in Sechault.

Unfortunately, upon returning home, such awards meant little to the general American populace. In February 1919, they returned to New York but were not allowed to participate in the same parade as the rest of the American soldiers, instead having their own separate march in the heart of Harlem itself. Soldiers such as Henry Johnson never received their promised benefits to the military, nor any medals, despite in Johnson’s case him having sustained 21 combat wounds. He would later fall into depression and die penniless in 1929, at the age of 36. He is now buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His was not the only case of injustice, unfortunately, such as Private Leroy Johnston, who would be lynched in Arkansas during the Elaine Massacre of 1919.

As Social Studies teacher Mr. Stephen Asbury points out, “Where’s the justice for them after putting their lives on the line for us?” These men served with distinction, and may their efforts be forever remembered.

Janie Boyden • Feb 12, 2022 at 9:31 pm

Nice article. I love reading about the contributions of African Americans….especially during Black History month. Thank you!